Archive

1884–Cartoon–Corie Stretton

James Blaine’s campaign for the Presidency in 1884 was surrounded by controversy. With his opponent, Grover Cleveland, portrayed as the ideal honest, good person, Blaine had a series of scandals that tainted his image and led to numerous political cartoons criticizing him. This particular cartoon references three of the major scandals he was involved with that proved he was not qualified to be the Republican Presidential candidate.

James Blaine’s campaign for the Presidency in 1884 was surrounded by controversy. With his opponent, Grover Cleveland, portrayed as the ideal honest, good person, Blaine had a series of scandals that tainted his image and led to numerous political cartoons criticizing him. This particular cartoon references three of the major scandals he was involved with that proved he was not qualified to be the Republican Presidential candidate.

The two of the weights on the trap depicted in this cartoon represent the Mulligan Letters and Little Rock Bonds. About fifteen years before the election, Blaine served as speaker of the house, and was involved in passing a land grant for the Little Rock and Fort Smith Railroad, however as a result he received a great deal of money in bonds from the company. Once the success of the railroad company eventually waned, he sold his bonds to another man, Tom Scott, and began supporting his railroad company, Scott’s Texas and Pacific Railroad, instead. This situation was discovered by one of the men working for the Little Rock railroad company, James Mulligan, who found copies of letters from Blaine to the head of the Little Rock railroad, detailing the crooked dealings Blaine was involved with. (“1884: Cleveland v. Blaine”). Aptly named the Mulligan Letters, these were published by newspapers throughout the country as Blaine began his campaign for the Presidency, greatly hurting his credibility. The fact that the phrase “Burn this letter!” was written at the bottom of one of the letters was even more revealing, and significantly influenced the public’s opinion of him.

The other weight on the trap in this cartoon is “Guano Statesmanship,” related to Blaine’s war record through the War of the Pacific. He petitioned to the U.S. to support Peru against Chile, however many people in government doubted his reasons for wanting to give aid to Peru. There were charges that he had personal investments in Peruvian guano and nitrates, which could be used as gunpowder during battle, and was motivated to help solely because of this reason (“1884: Cleveland v. Blaine- Blaine’s Scandal Sheet”). This also works to show his dishonesty and works to convince the American people that Blaine was solely focused on doing things for personal gain, as opposed to the well being of the country.

The other weight on the trap in this cartoon is “Guano Statesmanship,” related to Blaine’s war record through the War of the Pacific. He petitioned to the U.S. to support Peru against Chile, however many people in government doubted his reasons for wanting to give aid to Peru. There were charges that he had personal investments in Peruvian guano and nitrates, which could be used as gunpowder during battle, and was motivated to help solely because of this reason (“1884: Cleveland v. Blaine- Blaine’s Scandal Sheet”). This also works to show his dishonesty and works to convince the American people that Blaine was solely focused on doing things for personal gain, as opposed to the well being of the country.

Logan’s portrayal as a rat is in itself degrading, giving the impression that he is among the lowest forms of life that no one would or should support. As he reaches for the cheese under the trap, the “Presidency,” he will inevitably be crushed by his “o’erweening ambition,” or his cocky and arrogant goals for leading the country despite his many shortcomings. The title says it all by calling Logan “His Own Destroyer,” saying that his own actions in the past have destroyed any chance he has at winning the Presidency. Though he had experience in the government, these many scandals appear to weigh too much and will literally crush him before he can achieve his goals. The irony of the tagline at the bottom is obvious, calling it a “pleasant situation,” and adds to the impression that Blaine is not in any position to win the election. These details all combine to show to the public that Blaine is an immoral, self-centered, and ill prepared candidate compared to Cleveland.

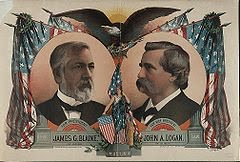

Another important part of this cartoon to note is the tail of the rat, Blaine, which has his Vice Presidential candidates name, “Logan,” written on it. Blaine did not have a solid relationship with his VP candidate, as they disagreed on a variety of topics, however the two of them were selected by the Republican convention to run as a team. Logan did not have nearly as many scandals on his record as Blaine did, which is why he worked to stress the integrity of past Republican Presidential candidates and prove that he and Blaine would continue that tradition (“1884: Cleveland v. Blaine”). Other than that minor contribution, however, he was not seen as having any kind of influence in the campaign, and was even sometimes ignored by Blaine. His representation as Blaine’s tail, then, shows just how insignificant he was to the campaign, and diminishes his power and credibility. Indeed, a Presidential candidate with a history of corruption with an unimportant candidate for Vice President certainly combines for an unsuccessful campaign, which is exactly what Cleveland’s campaign was hoping when they began their attacks on the Republican candidates. Though the results of the election were incredibly close, it is clear that these slander campaigns had a huge impact on voter’s decisions on election day.

Another important part of this cartoon to note is the tail of the rat, Blaine, which has his Vice Presidential candidates name, “Logan,” written on it. Blaine did not have a solid relationship with his VP candidate, as they disagreed on a variety of topics, however the two of them were selected by the Republican convention to run as a team. Logan did not have nearly as many scandals on his record as Blaine did, which is why he worked to stress the integrity of past Republican Presidential candidates and prove that he and Blaine would continue that tradition (“1884: Cleveland v. Blaine”). Other than that minor contribution, however, he was not seen as having any kind of influence in the campaign, and was even sometimes ignored by Blaine. His representation as Blaine’s tail, then, shows just how insignificant he was to the campaign, and diminishes his power and credibility. Indeed, a Presidential candidate with a history of corruption with an unimportant candidate for Vice President certainly combines for an unsuccessful campaign, which is exactly what Cleveland’s campaign was hoping when they began their attacks on the Republican candidates. Though the results of the election were incredibly close, it is clear that these slander campaigns had a huge impact on voter’s decisions on election day.

Sources:

http://elections.harpweek.com/1884/cartoon-1884-medium.asp?UniqueID=17&Year=1884

1868–Harper’s Cartoon–Justin Snow

Another example of campaign rhetoric from the 1868 election is another cartoon from Harper’s Weekly. Whereas the last pro-Grant cartoon portrayed Seymour as timid and almost innocently dumb, this one does the opposite. Seymour is depicted as Satan. Also present are Columbia and what appears to be a male voter. The voter is centered between the two, with Columbia trying to draw him towards the light and Seymour trying to draw him towards the darkness.

Another example of campaign rhetoric from the 1868 election is another cartoon from Harper’s Weekly. Whereas the last pro-Grant cartoon portrayed Seymour as timid and almost innocently dumb, this one does the opposite. Seymour is depicted as Satan. Also present are Columbia and what appears to be a male voter. The voter is centered between the two, with Columbia trying to draw him towards the light and Seymour trying to draw him towards the darkness.

Essentially, the cartoon claims that a vote for Grant is a vote for the “road to peace,” as is carved on a rock above Columbia. In contrast, a vote for Seymour is a vote for the “road to war and ruin.” To emphasize this, the side that features Columbia shows the Capitol Building and an open sky. There are Civil War memorials for the Union as well as farming tools, which seem to symbolize prosperity and economic growth.  Seymour, however, is shown with a tail and hoofs for feet like some kind of beast. His hair has been drawn in a way to make it appear like horns. Behind him is what seems to be the lynched corpse of an African-American. Blair can be seen sharpening a sword and above him is a bust of John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, with the words “slavery,” “CSA,” and “KKK” carved above him. There are several captions, one of which is Biblical. “Lead us not into temptation,” reads one. There are also several quotations that contrast Grant’s plea for peace with the rhetoric of Blair, demanding the president disperse the “Carpet-Bag State Government.”

Seymour, however, is shown with a tail and hoofs for feet like some kind of beast. His hair has been drawn in a way to make it appear like horns. Behind him is what seems to be the lynched corpse of an African-American. Blair can be seen sharpening a sword and above him is a bust of John Wilkes Booth, Abraham Lincoln’s assassin, with the words “slavery,” “CSA,” and “KKK” carved above him. There are several captions, one of which is Biblical. “Lead us not into temptation,” reads one. There are also several quotations that contrast Grant’s plea for peace with the rhetoric of Blair, demanding the president disperse the “Carpet-Bag State Government.”

This cartoon is a prime example of waving the bloody shirt. Republicans have directly linked the Democrats to the Confederates and the Ku Klux Klan. Not only that, they have taken it a step further and made the debate about a struggle between good and evil. Although the previous two examples of pro-Grant campaign rhetoric appeared to be far more focused on Grant’s character, making their allusions to Democratic collusion with the Confederacy minimal, this is far different. Its implication are blatant.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_presidential_election,_1868

http://elections.harpweek.com/1868/cartoon-1868-medium.asp?UniqueID=21&Year=1868

http://elections.harpweek.com/1868/cartoon-1868-medium.asp?UniqueID=5&Year=1868

1868–Tanner Cartoon–Justin Snow

The second piece from the campaign is a cartoon that ran in Harper’s Weekly during the campaign. It too alludes to Grant as a tanner, giving an indication that this was something the Grant campaign pushed quite hard.

In this pro-Grant cartoon, he is labeled “The Great American Tanner.” Grant is pictured with a ragged apron and a plain white shirt with the sleeves rolled up. He has a cigar in his mouth. He looks like the everyman. To his left are once again his three “references”: Lee, Pemberton, and Buckner. Each of them is holding their backsides like they’ve just had their hides tanned. To Grant’s right is Seymour and Frank Blair, the Democratic presidential and vice presidential candidates. Seymour looks timid with his hands folded and Blair looks somewhat ridiculous in an ordained uniform. They are both being escorted by New York gubernatorial candidate John Hoffman, who was the leader of of New York City’s Tammany Hall Democrats. This sect of the party tended to be more reform minded, which could be indicated by Hoffman’s native American dress.

In this pro-Grant cartoon, he is labeled “The Great American Tanner.” Grant is pictured with a ragged apron and a plain white shirt with the sleeves rolled up. He has a cigar in his mouth. He looks like the everyman. To his left are once again his three “references”: Lee, Pemberton, and Buckner. Each of them is holding their backsides like they’ve just had their hides tanned. To Grant’s right is Seymour and Frank Blair, the Democratic presidential and vice presidential candidates. Seymour looks timid with his hands folded and Blair looks somewhat ridiculous in an ordained uniform. They are both being escorted by New York gubernatorial candidate John Hoffman, who was the leader of of New York City’s Tammany Hall Democrats. This sect of the party tended to be more reform minded, which could be indicated by Hoffman’s native American dress.

The power of the Tammany Hall Democrats, which was associated with New York’s political machine, could also be indicated by Hoffman’s sheer size in comparison to Seymour and Blair. As he delivers the two to Grant, he tells him that there are two more hides to be tanned. Grant responds that he’ll finish them off in early November, meaning election day.

The power of the Tammany Hall Democrats, which was associated with New York’s political machine, could also be indicated by Hoffman’s sheer size in comparison to Seymour and Blair. As he delivers the two to Grant, he tells him that there are two more hides to be tanned. Grant responds that he’ll finish them off in early November, meaning election day.

Much like the first piece of campaign material, this cartoon works well. It reinforces the image the Grant campaign was trying to form of Grant as one of the people, a simple tanner who happened to become a good soldier. It also links the Democrats with the Confederates. Although this is not done directly, by making the Democratic nominees the next ones Grant needs to tan after three Confederate generals, it seems to group them as similar in nature. This indeed played a role in the campaign with the Civil War still fresh in the minds of many Americans and the Republicans running on the fact that many Democrats defected after Lincoln’s election and became members of the Confederacy.

http://elections.harpweek.com/1868/cartoons/AmericanTanner12w.jpg

1860–Cartoon–Sarah Moran

During the election of 1860, in a very divisive election, one thing was clear; the issue of slavery was tearing the country apart. This one issue divided the Democratic Party into Northern and Southern factions and caused the leading Republican candidate, Senator Henry Seward not to receive the nomination at the Republican Convention.

For my piece of rhetoric, I chose a cartoon that correctly depicted the weight that slavery had on the candidate’s shoulders during this election.

For my piece of rhetoric, I chose a cartoon that correctly depicted the weight that slavery had on the candidate’s shoulders during this election.

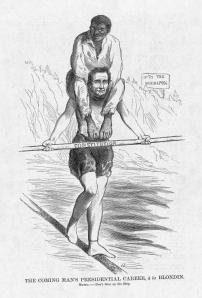

This cartoon recognizes a pop culture icon of the time, Charles Blondin. Blondin, a French acrobat, earned his claim to fame when he became the first person to cross Niagara Falls on a tight rope in 1959. After seeing the falls for the first time, Blondin knew he had to cross one of the world’s wonders on a tight rope. He refused to give up despite the many setbacks he faced including being denied permission multiple times to string the tight rope across the falls. Finally, on June 30, 1959, Blondin accomplished his goal… but he was not done yet. He continued to perform the stunt with added variations and larger crowds. Some of these stunts included, crossing with a blindfold, crossing on stilts and performing tricks mid-way through his walks! The walk the cartoon refers to happened on August 17, 1859 when Blondin crossed the falls with his manager, Harry Colcord, on his back (“Charles Blondin Biography”).

In the cartoon, Lincoln is pictured as Charles Blondin performing the walk with a slave on his shoulders, referencing the August 1859 walk (“The Coming Man’s Presidential Career, a La Blondin”). Lincoln is also shown holding a balancing rod labeled as The Constitution. This cartoon helps shed light on how the issue of slavery played out in the election of 1860. By placing the slave on Lincoln’s shoulders the cartoon symbolizes the burden and pressure slavery had on the Republican Party during the election. With a weakened Democratic Party, the issue of slavery was really all that stood in Lincoln’s way.

The Constitution serves as Lincoln’s balancing rod in the cartoon and explains the Republican’s stance on slavery at this time and the strategy they were using to win the election.

Headed into the Republican Convention in May 1860, Senator William Henry Seward from New York was thought to have the Republican nomination wrapped up. With the issue of slavery on the table, the Republicans knew they had to be strategic in choosing their candidate in order to win the election. The Republicans were made up of mostly ex-Whigs and moderates (“The Election of 1860”). Seward was known for his avid abolitionist mindset and goals. To ensure they did not isolate any members of the Party, the Republicans strategically went with the more moderate candidate on this issue, Abraham Lincoln (“The Election of 1860”).

Headed into the Republican Convention in May 1860, Senator William Henry Seward from New York was thought to have the Republican nomination wrapped up. With the issue of slavery on the table, the Republicans knew they had to be strategic in choosing their candidate in order to win the election. The Republicans were made up of mostly ex-Whigs and moderates (“The Election of 1860”). Seward was known for his avid abolitionist mindset and goals. To ensure they did not isolate any members of the Party, the Republicans strategically went with the more moderate candidate on this issue, Abraham Lincoln (“The Election of 1860”).

The balancing rod in the cartoon references Lincoln’s moderate stance on the issue of slavery and the Party’s use of the Constitution to not swing too far towards abolition. The Republicans opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories. Lincoln’s thought was that if slavery was prohibited in new territories it would eventually end in the states where it previously existed. The Republican Party even supported a Constitutional amendment disallowing further Congressional interference in slavery in the South. Lincoln also recognized the legitimacy of the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution and agreed with continued enforcement of this clause (“The Election of 1860”). The Fugitive Slave Clause guaranteed that any slave that escaped to another state must be returned to the original owner. The Constitution served as Lincoln’s balancing rod demonstrating his moderate stance on slavery keeping him from tipping towards abolitionism, which would have most likely cost him the election. This piece of rhetoric is unique in its use of a pop culture reference to explain the Republican’s stance of slavery.

Works Cited

“Charles Blondin Biography.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. Web. 20 Apr. 2011. <http://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-A-Bu-and-Obituaries/Blondin-Charles.html>.

“The Coming Man’s Presidential Career, a La Blondin.” Harp Week. Web. 20 Apr. 2011. <http://elections.harpweek.com/1860/cartoon-1860-large.asp?UniqueID=12>.

“The Election of 1860.” Tulane University. Web. 20 Apr. 2011. <http://www.tulane.edu/~latner/Background/BackgroundElection.html>.

1860–“Five Eras” Prints–Sarah Moran

With the election of 1860 looming, the weakened Democratic Party had divided into Northern and Southern factions. The leading Democrat in the North was Stephen A. Douglas while the leading Democrat in the South was John C. Breckenridge. The Republicans chose a more moderate candidate, Abraham Lincoln, to run on their ticket. Constitutional Union candidate, John Bell, rounded out the list of presidential hopefuls during the election of 1860 (“United States Presidential Election of 1860”).

With the election of 1860 looming, the weakened Democratic Party had divided into Northern and Southern factions. The leading Democrat in the North was Stephen A. Douglas while the leading Democrat in the South was John C. Breckenridge. The Republicans chose a more moderate candidate, Abraham Lincoln, to run on their ticket. Constitutional Union candidate, John Bell, rounded out the list of presidential hopefuls during the election of 1860 (“United States Presidential Election of 1860”).

With the nation divided over the issue of slavery, the Republicans did not even run a slate in most Southern states. The race in the South was between Democrat John C. Breckenridge and Constitutional Union candidate John Bell. The real race in the North was between Republican Abraham Lincoln and Democrat Stephen Douglas (“United States Presidential Election of 1860”). The two candidates had very different tactics and campaigning styles. Douglas was the first candidate to go on a nationwide speaking tour prior to the election. With his dark hair and piercing eyes, Douglas was known for his compelling speaking style that always commanded the attention of his audience with his intelligence and deep voice (“Stephen A. Douglas and the American Union”). In contrast, Lincoln did not campaign or give speeches of his own. The Republicans and their supporters, such as the Wide Awakes, ran pamphlets, leaflets and editorials throughout the North (“United States Presidential Election of 1860”).

Lincoln and Douglas, both with political roots in Illinois, had met in the political arena before. In 1858, Lincoln and Douglas battled for control of the Illinois legislature in a series of seven debates taking place in seven of the nine districts in Illinois (“Stephen A. Douglas and the American Union”). Slavery was the main issue discussed during these debates. Both candidates’ stances on slavery were the same in 1858 as they ran on in 1860. Lincoln opposed the abolition of slavery into new territories while Douglas supported popular sovereignty. At the end of the debates, Douglas was re-elected to the Senate but Lincoln had established a political foothold that would carry him through to the election of 1860 (“Stephen A. Douglas and the American Union”).

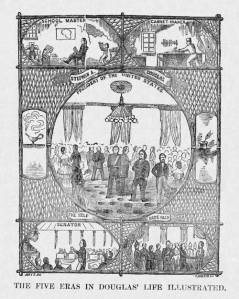

Experience proved to be a key aspect of the senate election and the Democrats used experience again to their advantage. The second piece of rhetoric I chose to focus on captures just that. This piece of rhetorical history was actually a two-part cartoon that appeared in “The Campaign Plain Dealer and Popular Sovereignty Advocate,” which was a popular Democratic campaign publication of the time. The first piece of the cartoon titled “The Five Eras in Douglas’s Life Illustrated” pictured different periods of Douglas’s life and appeared on July 21, 1860. The cartoon depicts Douglas’s earlier professional life as a cabinetmaker and a teacher. The bottom corners depict Douglas as a U.S. Senator and meeting Tsar Nicholas I during a political tour of Europe in 1853. Finally, the middle shows Douglas as President of the United States (“Five Eras in Old Abe’s Life Illustrated”). As your eyes travel down the page, the more grand and political the experience gets for Douglas all leading up to the middle of the cartoon, him becoming President of the United States.

Experience proved to be a key aspect of the senate election and the Democrats used experience again to their advantage. The second piece of rhetoric I chose to focus on captures just that. This piece of rhetorical history was actually a two-part cartoon that appeared in “The Campaign Plain Dealer and Popular Sovereignty Advocate,” which was a popular Democratic campaign publication of the time. The first piece of the cartoon titled “The Five Eras in Douglas’s Life Illustrated” pictured different periods of Douglas’s life and appeared on July 21, 1860. The cartoon depicts Douglas’s earlier professional life as a cabinetmaker and a teacher. The bottom corners depict Douglas as a U.S. Senator and meeting Tsar Nicholas I during a political tour of Europe in 1853. Finally, the middle shows Douglas as President of the United States (“Five Eras in Old Abe’s Life Illustrated”). As your eyes travel down the page, the more grand and political the experience gets for Douglas all leading up to the middle of the cartoon, him becoming President of the United States.

One week later, on July 28, 1860, “The Campaign Plain Dealer and Popular Sovereignty Advocate” came out with part two of “The Five Eras.” This cartoon depicted different periods of Republican candidate “Old Abe’s” life but in a condescending tone. The left corner depicts Lincoln as a rail-splitter, an image that is a recurrent theme used by both parties during the Campaign. The Republicans’ use it to their advantage to illustrate and draw upon Lincoln’s humble  background. One famous cartoon pictures Lincoln splitting his “last rail,” which is labeled as the Democratic Party, taking a shot at the divided party. The Democrats’ however, use it to mock Lincoln’s lack of political experience compared to Douglas. The top right corner depicts Lincoln as the “rear admiral” of a flat boat. The bottom of the cartoon depicts Lincoln being strangled by an Indian during the Black Hawk War and immediately next to it is Lincoln accepting the Republican nomination for President. The middle of the cartoon depicts Lincoln again as a rail-splitter implying that he lost the election and had to go back to his roots (“Five Eras of Old Abe’s Life Illustrated”). Part two is a direct attack on Lincoln’s lack of political experience in relation to his main challenger in the North, Stephen Douglas. In this cartoon, as your eyes travel down the cartoon Lincoln’s experience never grows in prestige like Douglas’ does.

background. One famous cartoon pictures Lincoln splitting his “last rail,” which is labeled as the Democratic Party, taking a shot at the divided party. The Democrats’ however, use it to mock Lincoln’s lack of political experience compared to Douglas. The top right corner depicts Lincoln as the “rear admiral” of a flat boat. The bottom of the cartoon depicts Lincoln being strangled by an Indian during the Black Hawk War and immediately next to it is Lincoln accepting the Republican nomination for President. The middle of the cartoon depicts Lincoln again as a rail-splitter implying that he lost the election and had to go back to his roots (“Five Eras of Old Abe’s Life Illustrated”). Part two is a direct attack on Lincoln’s lack of political experience in relation to his main challenger in the North, Stephen Douglas. In this cartoon, as your eyes travel down the cartoon Lincoln’s experience never grows in prestige like Douglas’ does.

Lincoln and Douglas were not new enemies on the political scene, dating back to their political roots in Illinois during the 1858 debates. Recurrent themes, especially that of experience, come back as dominant rhetorical strategies employed by the Democratic Party.

Works Cited

“Five Eras in Old Abe’s Life Illustrated.” Harp Week. Web. 20 Apr. 2011. <http://elections.harpweek.com/1860/cartoon-1860-Medium.asp?UniqueID=11>.

“Stephen A. Douglas and the American Union.” The University of Chicago Library. Web. 20 Apr. 2011. <http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/spcl/excat/douglas1.html>.

“United States Presidential Election of 1860.” Encyclopedia Virginia. 28 May 2009. Web. 20 Apr. 2011. <http://encyclopediavirginia.org/United_States_Presidential_Election_of_1860>.

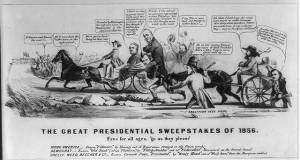

1856–Sweepstakes Cartoon–Dan Hawvermale

The political cartoon I choose is called The Balls Are Rolling – Clear the Track and is an attack on the Buchanan campaign. The theme of the cartoon is to attack Buchanan where he is at his weakest. The cartoon attempts to exploit political issues that have been negative for the Democratic Party as a whole and Buchanan personally. Many of the attacks are ones that have been in the “media” for some time at this point. Some might say that this cartoon had little impact because many of the issues were already known to the public. Many of the arguments against Buchanan stem from his relationship with Franklin Pierce and the Democratic Party.

The political cartoon I choose is called The Balls Are Rolling – Clear the Track and is an attack on the Buchanan campaign. The theme of the cartoon is to attack Buchanan where he is at his weakest. The cartoon attempts to exploit political issues that have been negative for the Democratic Party as a whole and Buchanan personally. Many of the attacks are ones that have been in the “media” for some time at this point. Some might say that this cartoon had little impact because many of the issues were already known to the public. Many of the arguments against Buchanan stem from his relationship with Franklin Pierce and the Democratic Party.

The way that the cartoon forms these attacks on Buchanan and the Democratic Party is by showing Buchanan being crushed by giant stone spheres. These stone spheres bear and etching of the states that are supposed to crush the Democratic campaign. The stone spheres are Maine, Vermont, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, Connecticut, Illinois, Wisconsin New Jersey, Michigan, Massachusetts, Rohde Island, New Hampshire and Indiana. Under all of these stone sphere states lies Buchanan, half sunk into a hole labeled “Cincinnati Platform.” Buchanan being crushed by the spheres exclaims “Oh Dear!_ Oh Dear! This Platform will be the death of me. I’m nearly crushed out already!” Footnotes in the cartoon explain that the balls may be intended to recall the giant ball of Locofocoism used to the derision of the Democrats in Whig cartoons of the 1840 presidential campaign.

In the back of the cartoon you can see into the distance which shows a burning town in Kansas, with families fleeing for their lives. Also in the distance are the Rocky Mountains, a railroad train going towards California, and the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Also on the upper left hand side of the cartoon is an eagle holding a banderole with Republican candidates’ names “Fremont” and “Dayton.” The eagle clutches bundled cartridge with the words “Union,” “Liberty,” and “Constitution” on it. To the right of the eagle is a banner strewn through the sky as if it were a rainbow stating “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Men & Fermont.” This was the Republican Party’s motto at the time of the 1856 election.

In the back of the cartoon you can see into the distance which shows a burning town in Kansas, with families fleeing for their lives. Also in the distance are the Rocky Mountains, a railroad train going towards California, and the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Also on the upper left hand side of the cartoon is an eagle holding a banderole with Republican candidates’ names “Fremont” and “Dayton.” The eagle clutches bundled cartridge with the words “Union,” “Liberty,” and “Constitution” on it. To the right of the eagle is a banner strewn through the sky as if it were a rainbow stating “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Men & Fermont.” This was the Republican Party’s motto at the time of the 1856 election.

Lying in front of the half sunk Buchanan are a pieces of paper strewn out stating various claims against Buchanan and the Democratic Party. Each of the papers refers to a different negative political event such as Kane Lecompte, Ostend, Polygamy and Slavery, Kansas bogus Laws, Border Ruffianism. Many of these topic refer to the democratic party’s treatment of Kansas regarding slavery. Fillmore is standing by Buchanan saying “Oh James! Erastus! Lying wont scare me, I hear the coming take me off the tack.” He is also holds two documents, the “Fugitive Slave Bill” and an “Albany Speech.” The fugitive Slave bill was a law that made it legal to come bring slaves back from northern free states. Many times southerners would come grab any black man the met the description of their slaves and take them back against their will. This along with the vehement enforcement of the law by Fillmore and his cabinet created a huge amount of resentment from northern states towards both Fillmore and the Democratic Party as a whole.

It is worthy to note that this cartoon aired in a relatively “Democratic newspaper.” The cartoonist normally did not draw cartoons in favor of Fremont and often drew cartoons depicting him in negative manner. This cartoon may have had a greater effect if it were shown to Northern states in a Republican newspaper.

It is worthy to note that this cartoon aired in a relatively “Democratic newspaper.” The cartoonist normally did not draw cartoons in favor of Fremont and often drew cartoons depicting him in negative manner. This cartoon may have had a greater effect if it were shown to Northern states in a Republican newspaper.

Sources:

https://dcl.umn.edu/search/search_results?search_string=political%20cartoon&per_page=12

1884–Political Cartoon–Corie Stretton

Unfortunately, the candidates who lose in Presidential elections throughout history are often forgotten. During the Gilded Age in American history, there was a series of elections that were decided by a fraction of the vote, which means that we could have very easily elected the other men who ran for the position. Despite this fact, their names are still mostly unknown. James Blaine is the perfect example of this, competing against Grover Cleveland in the 1884 election. While his campaign was surrounded by scandal, he still managed to come very close to beating Cleveland, losing the popular vote by only 0.3 percent.

Unfortunately, the candidates who lose in Presidential elections throughout history are often forgotten. During the Gilded Age in American history, there was a series of elections that were decided by a fraction of the vote, which means that we could have very easily elected the other men who ran for the position. Despite this fact, their names are still mostly unknown. James Blaine is the perfect example of this, competing against Grover Cleveland in the 1884 election. While his campaign was surrounded by scandal, he still managed to come very close to beating Cleveland, losing the popular vote by only 0.3 percent.

Many political cartoons were made in reference to Blaine’s embarrassing past, with this particular cartoon acting as a reference to a group of people called the Mugwumps. This was a group of politicians from the Republican Party who were displeased with Blaine as the Republican nomination for President, and crossed party lines to support Cleveland instead. They considered themselves to be reformers, and believed in Cleveland’s competency as a candidate much more than Blaine’s. They were soon known as “Mugwumps,” named after the Algonquian Indian word for an important, or self-important, person, and were subject to a great deal of criticism from the rest of their party. Indeed, there were other cartoons drawn that showed these politicians sitting on a fence with “their ‘mug’ on one side of the fence and their “wump” on the other. Sometimes, they were even referred to as “hermaphrodites,” or homosexuals, because they refused to support the party they came from (Frum). “Their actions were seen as a complete betrayal of the Republican Party, and contributing to Blaine’s eventual loss in the election.

This cartoon demonstrates the fear of the Republican Party, and how they were convinced that the Mugwumps would bring about the destruction of Blaine’s campaign. The scene is modeled off of a story from the Bible known as Belshazzar’s Feast. In this story, Belshazzar, the king, is having a great feast with many of his lords with a great deal of food and drink to go around. In the middle of this dinner, “fingers of a man’s hand” appeared and wrote a threatening message on the wall that his kingdom would be destroyed, while a voice spoke about how Belshazzar had dishonored his father before him as king. Later that night, Belshazzar was killed, and a new king took over the kingdom (“Belshazzar’s Feast Bible Story”).

This cartoon demonstrates the fear of the Republican Party, and how they were convinced that the Mugwumps would bring about the destruction of Blaine’s campaign. The scene is modeled off of a story from the Bible known as Belshazzar’s Feast. In this story, Belshazzar, the king, is having a great feast with many of his lords with a great deal of food and drink to go around. In the middle of this dinner, “fingers of a man’s hand” appeared and wrote a threatening message on the wall that his kingdom would be destroyed, while a voice spoke about how Belshazzar had dishonored his father before him as king. Later that night, Belshazzar was killed, and a new king took over the kingdom (“Belshazzar’s Feast Bible Story”).

Related to this story, the cartoon has the words “Republican Revolt” written on the wall in the middle of what appears to be a large feast for Blaine, his Vice Presidential candidate John Logan, and several over politicians. Blaine, tattooed in the countless scandals he was associated with, is trying to hide from the ominous message behind pieces of newspapers, with a scared look on his face. Like Belshazzar, Blaine would inevitably fail in his pursuits, and in this cartoon the Mugwumps are being shown as the ones responsible. In addition, Logan is laying next to him, trying to block the message with his hand while wearing what appears to be clothes similar to the Native Americans, once again drawing a connection to the term Mugwumps and its meaning in the Algonquian Indian language. Logan’s positioning also reinforces the idea that Logan is less powerful and less significant compared to Blaine, with him literally falling down below Blaine.

The expressions of the faces of the men seated at the feast have similar looks of fear, as they all appear to be backing away from the message or even fighting each other to run away. The ears of the men who are attempting to escape are enlarged to resemble rats, belittling their integrity and showing their cowardice. The “food” they are feasting on is called “Pension Pie” and “Monopoly Stew,” referencing Republican Party’s initiatives related to monopolies and pensions at the time. Labeling all of the individuals also worked to hold them accountable to the American public for supporting a supposedly doomed candidate. These characters range from the speaker of the New York assembly to the editor of the Chicago Tribune (“1884: Cleveland v. Blaine- The Writing on the Wall”). The magazine where this cartoon was published, Puck, tended to favor the Democratic Party, and this preference is made even more obvious in this cartoon.

Sources:

http://elections.harpweek.com/1884/Overview-1884-3.htm

http://elections.harpweek.com/1884/cartoon-1884-large.asp?UniqueID=54&Year=1884

http://www.hymns.me.uk/51-belshazzars-feast-bible-story.htm

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2010/01/bring-back-the-mugwumps/7842/

1856–Pro-Fillmore Cartoon–Dan Hawvermale

I choose to discuss this cartoon because it was one of the few pieces of presidential rhetoric that actually favored Fillmore in the presidential campaigning of 1856. Although he only received 1/5 of the overall vote Fillmore played an important role in the election stealing votes from both candidates thus making it a much closer race. At the time of the 1856 election the Whig party had fallen apart and Fillmore had no formal party to run for since he refused to join the Republican Party. With little options he chooses to run for the “Know Nothing Party” with Andrew Jackson Donelson as his vice president, who was the nephew of former president Andrew Jackson. Even though I stated earlier that Fillmore only accomplished receiving 20% of the vote, it was one of the most impressive showings from a third party candidate in history. It should also be noted that Fillmore was attempting to be nominated for a second, nonconsecutive term. This feat has only been accomplished by one president in history sir, Grover Cleveland., and is by no means an easy task.

I choose to discuss this cartoon because it was one of the few pieces of presidential rhetoric that actually favored Fillmore in the presidential campaigning of 1856. Although he only received 1/5 of the overall vote Fillmore played an important role in the election stealing votes from both candidates thus making it a much closer race. At the time of the 1856 election the Whig party had fallen apart and Fillmore had no formal party to run for since he refused to join the Republican Party. With little options he chooses to run for the “Know Nothing Party” with Andrew Jackson Donelson as his vice president, who was the nephew of former president Andrew Jackson. Even though I stated earlier that Fillmore only accomplished receiving 20% of the vote, it was one of the most impressive showings from a third party candidate in history. It should also be noted that Fillmore was attempting to be nominated for a second, nonconsecutive term. This feat has only been accomplished by one president in history sir, Grover Cleveland., and is by no means an easy task.

In the cartoon I choose we see Fillmore with a much more optimistic view on the presidential race than the 205 he actually received in the end. In the cartoon Fillmore is in the leading carriage uttering the words “Founded by Washington the only sure Line to Washington is the American Express,” while his driver concurs, “We’ve got a sure thing on this race.” This is ironic considering the final outcome of the election, but the real comedy in the cartoon lies in its depiction of the other candidates.

In the cartoon I choose we see Fillmore with a much more optimistic view on the presidential race than the 205 he actually received in the end. In the cartoon Fillmore is in the leading carriage uttering the words “Founded by Washington the only sure Line to Washington is the American Express,” while his driver concurs, “We’ve got a sure thing on this race.” This is ironic considering the final outcome of the election, but the real comedy in the cartoon lies in its depiction of the other candidates.

The cartoon depicts Fillmore’s opponent James Buchanan and his incumbent predecessor Franklin as tag teaming the horse race. As a metaphor to Franklin’s endorsement of Buchannan’s running for president, he is seen carrying piggyback style during the race. Buchanon voices his worries to Pierce saying “Frank, I am afraid we aint got legs enough to beat Fillmore, but its some comfort to see old Greelys team stuck in the mud.” This is Buchanan voicing his concerns about the fact the Fraklin Peircee couldn’t even win his own re-nomination for the party.

Buchanan also refers to “Greelys team”, which is John C. Fermont’s campaign who is stuck in pool of mud labeled “Abolition Cess Pool.” Leading his carriage is New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley who is trying to pull the “nag” out of the mud with the carriage. The “nag” is a symbol for abolitionist all over the country and represents Fremont being lead blindly by abolitionist promoters. Abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher tries to force the back wheel using a rifle as a lever. As he attempts to pry the carriage free he yells to Horace Greenly “Brother Horace jerk his [i.e., the nag’s] head up once more and Shriek for Kansas, and I’ll give the wheel a pry with my rifle.” The reference is to Republican attempts to exploit the Kansas violence as an election issue, and also to Beecher’s arming of antislavery settlers in Kansas. Horace greenly replies to Beecher “It’s no use crying Kansas any more it don’t Prick his Ears a bit–I guess we’re about used up.” Fremont hears the two of them bickering and exclaims “Oh that I had kept the road & not tried to wade through this dirty ditch, but these fellows persuaded me, it was a shorter Way–and so I’ve gone it blind.” This shows his disappointment about choosing to support anti-slavery measures and making it a part of his campaign.

Bcuhanan himself in the cartoon expresses his concern regarding his ability to carry the party with which Franklin Pierce replies with his own concerns about not being re-nominated for the party, exclaiming “I don’t see how my party expect me to carry this old platform in, a winner, when they thought I had’nt legs enough to run for myself.” A by stander in the crowd mocks Pierce carrying Buchanan saying “I say Pierce aint that platform heavy?” The other members of the crowd are yelling as well. It is also worthy to note that this cartoon was aired in the newspaper Nathaniel Currier, in a few months prior to the 1856 election.

Bcuhanan himself in the cartoon expresses his concern regarding his ability to carry the party with which Franklin Pierce replies with his own concerns about not being re-nominated for the party, exclaiming “I don’t see how my party expect me to carry this old platform in, a winner, when they thought I had’nt legs enough to run for myself.” A by stander in the crowd mocks Pierce carrying Buchanan saying “I say Pierce aint that platform heavy?” The other members of the crowd are yelling as well. It is also worthy to note that this cartoon was aired in the newspaper Nathaniel Currier, in a few months prior to the 1856 election.

Sources:

1868–Campaign Card–Justin Snow

The election of 1868 saw Civil War hero and Republican nominee Ulysses S. Grant poised against Democratic Governor Horatio Seymour of New York. This was just three years after the end of the war and assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Being the first election since the war’s end, rhetoric surrounding the Confederacy ran high and Republicans used their martyred president to their advantage against Democrats, who were largely painted as compatriots of the Confederates.

The first example of campaign rhetoric is a campaign card issued by the Grant campaign in 1868. It is also an excellent example of social campaigning.

The first example of campaign rhetoric is a campaign card issued by the Grant campaign in 1868. It is also an excellent example of social campaigning.

The campaign card capitalizes on Grant’s military record as well as his humble roots. Before his service in the military, Grant was largely unsuccessful in everything he did. The son of a tanner, he worked in his father’s tanning shop in Illinois as a young man before the Civil War. Tanners were leather workers. They created such things as saddles, belts, gloves, and other leather goods. They also skinned the hides of cows and stretched and dyed them to create leather. In the campaign card, the Grant campaign uses this to make an analogy towards Grant’s opponents. The card reads that Grant and his vice presidential nominee, Schuyler Colfax, “respectfully inform the People of the United States that they will be engaged in Tanning old Democratic Hides” until after election day 1868. In this segment of the text, Grant, who was highly popular in the north after the end of the Civil War, is being projected to crush his Democratic opponents in the election. But instead of phrasing that in plain language, they allude to Grant’s roots as a tanner and the impressions many held of that work, which most voters would have been aware of at the time. The following line enforces the fact that Grant has experience in that field.

At the bottom of the card several references are listed as if this truly were a business card given to someone in need of a tanner. The references include General Buckner, who was Simon Bolivar Buckner, a Confederate general from Kentucky who surrendered Fort Donelson to Grant in 1862. The second reference is General Robert E. Lee, the commanding Confederate general of the Army of Northern Virginia who famously surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, bringing a close to the Civil War in the eastern theatre. The third and final reference is General Pemberton, who surrendered the city of Vicksburg to Grant in the summer of 1863 after a several month long siege. (Interestingly enough, Pemberton is considered the founder of Coca-Cola. A surgeon from Atlanta, Pemberton created a coca wine to ease wounded soldiers’ addiction to morphine. His concoction would later become Coke.)

At the bottom of the card several references are listed as if this truly were a business card given to someone in need of a tanner. The references include General Buckner, who was Simon Bolivar Buckner, a Confederate general from Kentucky who surrendered Fort Donelson to Grant in 1862. The second reference is General Robert E. Lee, the commanding Confederate general of the Army of Northern Virginia who famously surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, bringing a close to the Civil War in the eastern theatre. The third and final reference is General Pemberton, who surrendered the city of Vicksburg to Grant in the summer of 1863 after a several month long siege. (Interestingly enough, Pemberton is considered the founder of Coca-Cola. A surgeon from Atlanta, Pemberton created a coca wine to ease wounded soldiers’ addiction to morphine. His concoction would later become Coke.)

The Grant campaign’s rhetoric is quite clever. It works on various levels but particularly because it’s funny. These are names many voters would know after having fought in the war a few years before or followed it in the newspapers. As such, the Grant campaign is able to allude to his military record as a hero without ever once mentioning the war directly. Indeed, the only military reference is the prefix of general before the three reference names. Not even Grant is referred to as a general, merely a tanner.

The Grant campaign’s rhetoric is quite clever. It works on various levels but particularly because it’s funny. These are names many voters would know after having fought in the war a few years before or followed it in the newspapers. As such, the Grant campaign is able to allude to his military record as a hero without ever once mentioning the war directly. Indeed, the only military reference is the prefix of general before the three reference names. Not even Grant is referred to as a general, merely a tanner.

The use of a campaign card does several things as well. Not only is it furthering the humor of the text by acting as a kind of business card, it is also something that could be distributed to numerous people at events like fairs or parades. As such, it is a very personalized and social piece of campaign material and rhetoric that foreshadows the mailers that many campaigns use today

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e4/Card1868USElectionGrantAndColfaxTanners.jpg

1884–Cleveland as “Pa”–Corie Stretton

The 1884 election occurred during the Gilded Age in American history, where there was a series of Presidential elections that were very close in terms of the Electoral College, as well as the popular vote. Though candidates did not campaign in the same way that people today view campaigning, there were certain pieces of rhetoric that were very common for the time. One of the most popular forms of campaign rhetoric was political cartoons, which often directly attacked the candidate’s personal lives. This particular cartoon criticizing the Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland is the perfect example of a typical political cartoon for the late 1800s. The focus of this election quickly turned away from the candidate’s political views and focused mostly on their personal lives and the scandals that ensued.

The 1884 election occurred during the Gilded Age in American history, where there was a series of Presidential elections that were very close in terms of the Electoral College, as well as the popular vote. Though candidates did not campaign in the same way that people today view campaigning, there were certain pieces of rhetoric that were very common for the time. One of the most popular forms of campaign rhetoric was political cartoons, which often directly attacked the candidate’s personal lives. This particular cartoon criticizing the Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland is the perfect example of a typical political cartoon for the late 1800s. The focus of this election quickly turned away from the candidate’s political views and focused mostly on their personal lives and the scandals that ensued.

Entering into the 1884 election, Cleveland was very clearly favored to win. His “reformism” stressed his dedication to hard work and honesty, which made him a very endearing candidate in the eyes of both Democrats and Republicans (“Grover Cleveland (1837-1908)”). He also stood up against Tammany Hall, a Democratic political group from his home state of New York, which worked to promote immigrants into government positions; this move gained a lot of support from the middle class, and added to his positive image in the press. This cartoon, however, worked to completely change how he was viewed.

The story behind this cartoon is known as the Maria Halpin Affair. In July of 1884, rumors began circulating around the country that Cleveland was involved in a sex scandal with Maria Halpin, a widow who supposedly fathered his child out of wedlock about ten years ago. It was also said that he not only abandoned the mother and child, but also placed the child in an orphanage and sent the wife to an insane asylum. Cleveland later admitted to the truthfulness of the accusations made against him, however he denied that Halpin was placed in an asylum, claiming instead that she went to a half-way house due to her alcoholism. He also would add that he had financially supported the mother and son until she was sent to the half-way house, at which point his son was adopted by “a wealthy couple” (“1884: Cleveland v. Blaine”). Because he prided himself on his honesty, Cleveland had no choice but to admit to this behavior, but the Democratic campaign continued to twist the details of the situation to make Cleveland seem more like a responsible adult who was merely looking out for the future of his child.

This cartoon, which was published two months prior to election day in September of 1884, portrays Halpin as a clearly distressed, upset woman holding the son she allegedly had with Cleveland, with the child crying, “I want my Pa!” This soon became the slogan for the Republican party, chanting “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa?” at Cleveland; the Democratic party, however soon added to the chant to say, “Gone to the White House, ha ha ha!”. Though much was unknown about Halpin, mostly because no reporters ever interviewed her about the situation, this cartoon chooses to portray her as a well-dressed, sophisticated woman who cannot even look at Cleveland, and is trying to hold her innocent child away from him. Indeed, the fact that the child is dressed in white is also significant, stressing the innocence of the child born out of wedlock. This part of the image works to create even more sympathy for her in this situation, showing her as a woman the public can relate to rather than the alcoholic the Cleveland campaign wanted people to believe she was.

Cleveland, on the other hand, looks unintelligent and unprofessional, standing in an odd way with mismatched clothes and an angry, confused look on his face. This is in direct contrast with how he was normally portrayed, as a moral and honest person. There is even a tag on his jacket that reads “Grover the Good,” emphasizing further that his positive reputation was not well deserved and pointing to the contradiction displayed in this cartoon. The tagline at the bottom of the page reads, “Another voice for Cleveland,” showing the public that there was a previously unheard “voice” calling for Cleveland’s attention, particularly his son born from an extramarital affair. The cartoon is very direct about the message it is trying to send, demonstrating that Cleveland is not as moral as most people may believe, and that he is an incompetent Presidential candidate. Though Blaine was connected to a series of scandals, this particular one that Cleveland admitted to being involved in deeply affected his campaign, with Cleveland only winning the popular vote by 0.3 percent.

Cleveland, on the other hand, looks unintelligent and unprofessional, standing in an odd way with mismatched clothes and an angry, confused look on his face. This is in direct contrast with how he was normally portrayed, as a moral and honest person. There is even a tag on his jacket that reads “Grover the Good,” emphasizing further that his positive reputation was not well deserved and pointing to the contradiction displayed in this cartoon. The tagline at the bottom of the page reads, “Another voice for Cleveland,” showing the public that there was a previously unheard “voice” calling for Cleveland’s attention, particularly his son born from an extramarital affair. The cartoon is very direct about the message it is trying to send, demonstrating that Cleveland is not as moral as most people may believe, and that he is an incompetent Presidential candidate. Though Blaine was connected to a series of scandals, this particular one that Cleveland admitted to being involved in deeply affected his campaign, with Cleveland only winning the popular vote by 0.3 percent.

Sources:

http://elections.harpweek.com/1884/Overview-1884-3.htm

http://millercenter.org/president/cleveland/essays/biography/3